Matt Hartman

“It’s—it’s been rough,” Katrina Herrera said in late December 2020.

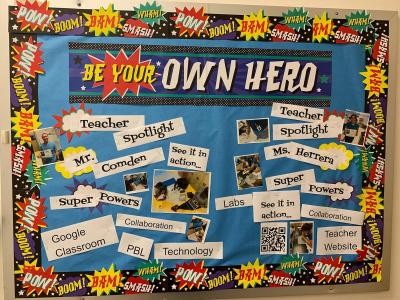

It was the last week of the fall semester at East Garner Magnet Middle School, where Herrera teaches science. The Wake County, North Carolina, school had moved to remote learning, so Herrera taught virtually all year long. Course schedules, lesson plans, activities: they were all upended.

But Herrera was resilient, as were thousands of other public school teachers around the country. “I think it was easier to prepare for because we had March through June to mess everything up,” she said, laughing. “We had that time in the spring to play around with different tools and apps and other platforms.”

In other words, she adapted. And she was helped by her training in Duke University’s Master of Arts in Teaching program, which she completed in 2016. “Ever since I started teaching I have been pretty reflective, and that part comes from the program,” Herrera said.

Each class, each mistake, each experience became an opportunity to learn and improve—a skill that proved essential in a school year like no other, when students needed more support than ever.

Founded in the 1960s and reconstituted in 1989, the MAT program is a year-long graduate degree that prepares candidates to become licensed secondary school teachers. Through a partnership with Durham Public Schools, every MAT graduate completes a 27-week internship split across two different schools with two different mentor teachers.

“I don’t know of another MAT program that does that,” said Julianne Hall, a science teacher at Durham School of the Arts who also graduated from Duke’s MAT program in 2016. “The value of that can’t be overstated. You really can’t beat 27 weeks of classroom experience.”

Hall dreamed of becoming a teacher since she worked as a teaching assistant as an undergraduate. She then taught for a summer with the teaching-training program Breakthrough Collaborative before coming to Duke. By that point, teaching felt natural, but those 27 weeks were still essential. “I learned the most about teaching from actually teaching,” she said.

The internship was also incredibly difficult. MAT candidates have to complete graduate coursework while working in the classroom—and for most, it’s their first time teaching. It’s a challenging experience, even with the help and support of mentor teachers, Duke faculty and a collaborative cohort. “I was being pulled in eight different directions,” Hall said. “That MAT year was the most exhausted I have been.”

Yet program alumni say that’s also a benefit. “It can feel like a lot, but I think that’s some of the best preparation for becoming a teacher,” said Jessica Friedlander, a 2014 MAT graduate who now teaches history at Riverside High School in Durham, North Carolina.

Even without a pandemic, teaching is a demanding profession involving long days of lesson planning and grading and constant adaptation to changing student needs. Friedlander said she worked nearly 80 hours a week during her first few years in the classroom. “You put in that hard work up front, and then [the time commitment] dwindles off,” she added.

But one thing remains constant, which makes all of that work worth it: the students. Since he was in college, Xavier Adams has been working with high school students. He originally planned on doing religious nonprofit work after graduating from Duke Divinity School in 2019. But then he realized he could have a bigger impact as a teacher.

“School is required,” he said. “Students are required to show up every day, so I just really enjoy the possibility of being embedded in their daily lives—to have an impact and be a support system for them.” He completed the MAT program in 2020 and is now a history teacher at Orange County High School in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

It’s no accident that Adams and so many of his fellow MAT alumni are working in public schools. The program emphasizes culturally responsive education that is built on strong relationships with students, so it attracts teachers who are committed to the mission of public education.

“I’ve really come to value how public education is so important to the integrity of democracy,” Adams said. “It’s critical that students are aware of the world they live in and how we got to this point. And also that they have the resources to do their own research. Public education really becomes a means to empower students to live fuller lives.”

Many MAT alumni continue to support that mission beyond their standard classroom duties, as well. Adams is teaching an African American Studies course after students advocated for it. Friedlander leads an equity in advanced academics team, and Herrera—who did a joint MAT-Environmental Management degree—focuses on environmental education, specifically with the goal of creating equitable opportunities in the field.

“I want to ensure that especially Black girls are not afraid to be outside and not afraid to be scientists,” Herrera said. “I want them to know that they are scientists, that they can play around in the dirt with worms and look at butterflies.”

The MAT program supports those efforts with two public school–specific fellowships. The Durham Teaching Fellowship provides a full scholarship plus monthly stipend for graduates who teach at Durham Public Schools for two years after graduating, and the Robert Noyce Teacher Fellowship offers tuition support, a monthly stipend and ongoing training for STEM teachers who work in a high-needs public school district.

Prepared with those resources, their 27 weeks of internship, pedagogical training and an extensive network of mentors and fellow alumni, MAT graduates have been able to continue building strong relationships with their students—even if they’re only seeing each other over Zoom.

“There’s some cool stuff you can do online, but you can’t hug a kid, you can’t high five a kid,” Friedlander said. “It’s just not the same. But thinking about my Duke MAT time, the largest component I took away is being reflective practitioner. I’ve taken that into the present day, and a large portion of it has been on the social-emotional needs of my students. I’ve had to really think about what they need to know, about what would be helpful to navigate this time and how to give them hope.”