Duke Today

Within just a few months, the Duke students in professor Louise Roth’s Biology of Mammals class have certainly learned their way around a skull. They can sketch and label the parts of any cranium, from a rat to a rhino.

But one mysterious set of bones has them scratching their heads.

It’s not the hippo, its bulging eye sockets set high on its head to help it see above water. Or the Ice Age mammoth, with its massive 20-pound molars.

It’s the cetaceans -- the group that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises -- that have them puzzled. “We’re weirded out by these skulls,” one student says, eyeing a table laid out with the white bony jaws and crania of a dolphin, a pilot whale, and other close relatives.

They all have two eye sockets, a mouth, and a nose. But the parts aren’t where they’re supposed to be.

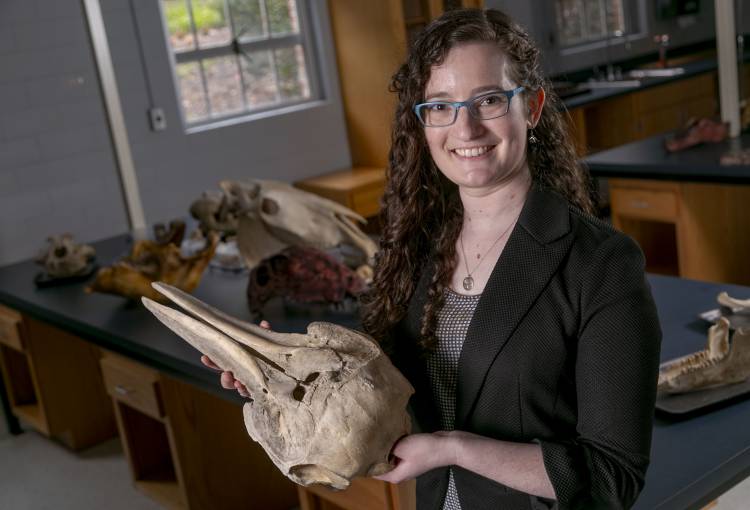

“Where’s the nose?” Roth’s Ph.D. student Rachel Roston asks a group of undergraduates gathered around the table. “Here?” says one student, pointing to the tip of one dolphin’s snout. It’s a reasonable guess. But a dolphin’s nose sits on top of its head.

And good luck finding the forehead. In most mammals, the flat bones of the skull fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. But in dolphins and their kin, the central bones of the face and forehead overlap and lie on top of one another. As a result the forehead is almost unrecognizable from the outside, because the bones have ‘slipped’ over each other like a collapsible spyglass -- a phenomenon known as telescoping.

“That’s crazy,” one student says.

These are among roughly four dozen specimens on display in a teaching lab in the Biological Sciences building. They range from the narrow, long-nosed skull of a horse to the broad, stocky skull of a pig or small skull of a rabbit, its eyes facing sideways to see danger approaching from any direction.

Though they come in different sizes and shapes, most of them are made up of the same bones in the same relative positions, Roth says. But not the group that dolphins belong to.

“Cetaceans seem to break away from this structural theme, and produce skulls that look unlike the skulls of any other mammal,” Roth says. “They are very strange-looking.”

That whales, dolphins and porpoises have weird skulls is hardly news to biologists. The earliest known reference to “telescoping” cetacean skulls dates back nearly 100 years ago. Over the decades, Roston says, the term has been used to describe different aspects of their cranial anatomy, from the stacking and moving around of the bones to the reorientation of the seams between them.

But for Roston and Roth, the question is: how did they get this way?

Some previous researchers have attributed the bones’ extensive overlap to the force of the water pushing on a whale or dolphin’s snout as it swims through the water. Others have suggested that, as the nasal passage migrated to the top of the skull to form the blowhole, perhaps it dragged other bones with it.

The team decided to take a fresh look, incorporating new fossil discoveries and advances in non-invasive imaging that make it possible to study how skulls grow in 3-D.

CT scans of developing dolphins and whales show that their skull bones start to overlap in the womb, long before their own swimming puts pressure on the skull, the researchers report in a study published earlier this year in the journal The Anatomical Record.

Findings also suggest that, while all cetacean skulls have overlapping parts, the specific bones involved varied as the ancestors of the two major cetacean groups -- toothed whales and baleen whales -- went their separate ways.

The first set of students have turned their attention to the peglike teeth of a river dolphin when another group shows up. Roston greets them with a mischievous grin, points to the array of skulls and says, “Where would the eyes be?”

This research was supported by the Stephen A. Wainwright Endowment Fund and Duke University’s Arts & Sciences Council on Faculty Research.

CITATION: "Cetacean Skull Telescoping Brings Evolution of Cranial Sutures into Focus," Rachel A. Roston and V. Louise Roth. The Anatomical Record, February 8, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24079