Diversifying Computer Science, One Cohort at a Time

When Cultural Competence in Computing (3C) Fellows first opened its application, the program’s leadership was hoping to bring 20 computer science faculty into their first cohort. Instead, after just two days, they had nearly 80 applicants.

“Overwhelmed—that was the first response,” said Nicki Washington, the program’s director and a professor of the practice of Computer Science at Duke.

The numbers kept growing. By the time they stopped accepting applications, 3C had 144 fellows from 67 different organizations across four countries. It wasn’t just faculty, either. Graduate students, university IT staff, public school officials, high school teachers and museum employees signed up, too. Entire university computer science departments joined together.

Over the next five months, those individuals will come together to complete 3C’s professional development program, which provides expert training in identity-inclusive topics to improve computing diversity, equity and inclusion. They will cover ways of understanding race and gender, white supremacy, intersectionality and various forms of oppression, as well as how that knowledge can improve computer science in practice.

“I think there’s value in all of these different levels that these people bring to the table,” Washington said. “It’s important for them to engage—particularly for graduate students who will become faculty and fan out to these other institutions.”

If Washington and her colleagues succeed in their mission, 3C will keep growing into a core component of movement to diversify their field.

The 3C program has its roots in Washington’s research, which is focused on identity and broadening participation in computing. As racial justice uprisings spread across the country in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Washington posted on a professional listserv about her Race, Gender, Class & Computing course. She was inundated with requests for the curriculum.

“I hesitated and pushed back, because it took a lot of time and work to put together the material,” Washington said. “Some of it I pulled from lived experience, and other things I had to learn. For me, it was: How do you put together something that prepares faculty, but doesn’t just give it to them and expects them to do it on their own?”

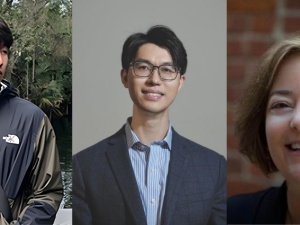

Washington’s answer was building a program that centers the perspectives and expertise of Black women. Shortly after joining the Duke faculty last summer, she reached out to Shaundra Daily, associate professor of the practice in Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) and Computer Science, combining forces for the work. And Cecilé Sadler, a graduate student in ECE, joined when she contacted Washington about an opportunity to get involved as an independent study.

“I think that’s something that makes what we’re doing so valuable and so unique,” said Sadler. “The current buzzwords around institutions, organizations and society at large are diversity, equity, inclusion and anti-racism, but I have yet to see a group teaching these topics that is led by three Black women.”

The curriculum they devised follows suit. The first half of the program focuses on identity, and the second on applying those insights to the field of computer science education—including sessions on mentoring students, faculty hiring and retention and teaching contentious issues. In all cases, Black women lead the way. Guest speakers—who are also mostly Black women—include leading scholars like Duke’s Jennifer Nash, UCLA’s Safiya Noble, Princeton’s Ruha Benjamin and others.

“The overall goal was always to change computing department cultures,” Washington said. “And to change it often requires decentering the students who are most marginalized.”

Washington explained that most STEM diversity initiatives focus on increasing “the pipeline” of students from marginalized backgrounds or creating interventions for students, like preparatory courses. But almost none of those address the bias they face from faculty and peers (including their classmates and TAs), she said.

“If you really want to make change, you have to start with the faculty,” she added. “If we’re not going to focus on improving how faculty engage with systemically marginalized groups, then all of these other efforts are going to continue to be only marginally effective.”

The program’s first cohort—and the overwhelming demand for a spot in it—offers cause for optimism. But the 3C leadership knows there’s a long fight ahead. “There haven’t been any anti-racist efforts in computing,” Washington said. “Black people especially have been screaming about this for the longest, and these were ignored and people further marginalized until they were pushed out of the field or silenced.”

By making use of the current national attention to racism, and including oppression based on other identities, 3C hopes to finally right that wrong and build inclusive computing departments. “I think the events of 2020 created the perfect storm and reinforced the need for this program’s birth,” Sadler said. “I am particularly hopeful about the next cohort, and eager to see if the widespread interest we had the first time around will continue through future cohorts.”

They’ve already started planning for the second cohort, but that’s only the beginning. Washington leveraged her start-up funding to get 3C off the ground, and she is now currently seeking financial support to expand it into a “hallmark program.”

“I want it to be an initiative that everyone knows they can come to and get what they need—be it training, additional opportunities like panels, maybe even expanding into K-12 education,” Washington said. “I always saw it growing into this huge research area and focus that centers these topics.”

If 3C succeeds, computer science departments across the country won’t just care about diversity, equity and inclusion when tragedy strikes. It will be an ongoing feature, changing departments cohort by cohort.

“My goal is to not allow people to take their eyes off the ball,” Washington said.