For 50 Years, the Center for Jewish Studies Has Delivered Interdisciplinary Insight

When Judah Goldin was named Duke’s first chair of Jewish Studies in 1943, the program was housed in the Graduate School. Twenty-nine years later, the Center for Jewish Studies was established—thanks to two visionaries, two universities and a host of generous donors.

Today, as the Center for Jewish Studies celebrates its golden anniversary, it has become a world-renowned interdisciplinary program offering an undergraduate certificate in Jewish Studies and supporting master’s and doctoral candidates across Duke.

Looking forward, the current director of the Center for Jewish Studies, Laura Lieber, professor of Religious Studies, wants to continue serving the ideals that the center has honored for half a century: robust and meaningful opportunities for undergraduates to take with them into the world, continued interdisciplinary programming and community enrichment with guest speakers and artists who address current cultural and political movements.

“Through this interdisciplinary approach to Jewish studies, we’re creating relationships across Duke,” says Lieber, a scholar of classical Judaism. “Students who might not necessarily meet while on campus, because of their diverse interests, can meet because they are all working, at some level, on Jewish studies.”

In the beginning

In 1969, Eric M. Meyers, the Bernice and Morton Lerner Distinguished Emeritus Professor in Judaic Studies, was only somewhat familiar with North Carolina: As a doctoral candidate at Harvard University, he had driven through the state on his way to a family vacation in Florida.

But when a job posted in Duke’s Department of Religious Studies, his Harvard mentors, also familiar with Duke, encouraged him to apply.

At the time, only a handful of universities had Jewish studies programs. “Now, try finding a school without one,” Meyers says.

While teaching courses on Ancient Near Eastern studies and the Old Testament, Meyers was approached by Emanuel “Mutt” Evans, the first Jewish mayor of Durham. Evans shared his dream of starting a joint program in Judaic Studies between Duke and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — and Meyers was sold.

The pair hit the road, traveling throughout North Carolina and New York to raise funds for an endowment supporting their shared vision. In 1972, the Cooperative Program in Judaic Studies was established, with Kalman Bland from Indiana University joining Meyers in Durham.

For five years, Bland and Meyers taught at both Duke and UNC-Chapel Hill as the endowment, the class sizes and the diversity grew.

“We taught an Intro to Judaic Civilization course that was at capacity, with mostly non-Jewish students,” Meyers says.

In 1977, the two universities parted ways, and the growing Duke faculty went to work building the Judaic program.

Digging in the dirt

One of the earliest recruits was Professor Emerita of Religious Studies Carol L. Meyers, who joined Duke as a part-time lecturer in 1976.

She also happens to be Meyers’ wife. The two met on the campus of Wellesley College at shabbat, a traditional Jewish Friday night meal. He was a cantor. She heard him singing, and they’ve been together ever since.

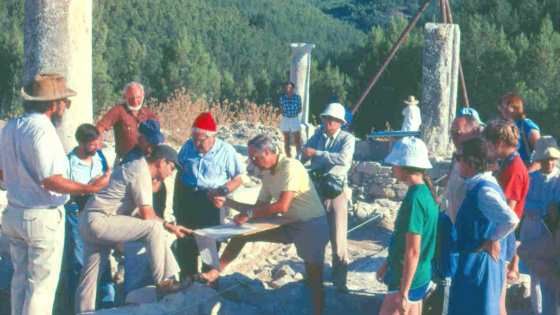

Sharing his passion for archaeology, the pair created the Duke Diggers Program in 1970, which afforded thousands of Duke students the opportunity to work on excavation sites throughout the Middle East.

While the Duke Diggers enjoyed discovering the rare finds — such as the Torah ark at Nabratein in 1981 and the Mona Lisa of the Galilee mosaic in 1986 — the far more common household antiquities were no less important.

The Meyers firmly believe that “digging in the dirt” confronts the past in a unique way for students. Students gain the invaluable, hands-on experiences that help them understand how people actually lived.

And the time spent on excavation sites can be the most important learning experiences in a student’s life — no matter what future career paths are unearthed.

For Rachel Rosenthal, an alumna who majored in Jewish text and tradition through Program II, the Diggers Program was indeed life changing. As an environmental lawyer, Rosenthal provides legal advice on a range of environmental concerns across the United States.

Advising on the laws concerning cultural resources management, and in particular, the protection of archaeological resources, Rosenthal works with technical project staff, archaeologists and Indian tribes on projects that might affect archaeological sites of importance to those Tribes.

“What’s made a huge difference in my career is my experience in the Duke Diggers Program, and digging with the Meyers in Israel,” she explains.

“From them, I learned a lot about the technical aspects of archaeology, as well as best practices for handling sensitive situations that arise in the field (like the discovery of human remains). Now that I give legal advice related to cultural resources management, especially the management of archaeological resource, I use what I learned from them all the time.”

Jewish studies today

Much has changed in 50 years.

Although the Diggers Program ended when the Meyers retired, it established a model for experiential learning in Jewish studies. Today’s undergraduates can spend a semester or a year abroad at a location of Jewish significance, or a summer studying Yiddish or Hebrew through embedded travel courses.

In addition, the Undergraduate Research Studies program provides meaningful opportunities for students to conduct independent research. The Center has funded projects from senior honor theses to internships with Yad Vashem — even a mobile app created for the Holocaust Speakers Bureau.

“These are unparalleled opportunities which allow our students to be in the field, focusing on their research with no restrictions,” says Serena Bazemore, executive director for the Center for Jewish Studies.

Over the years, the Center has deepened its relationships across campus, too. The Perilman Post-Doctoral Fellowship brings scholars who enrich Duke’s intellectual life, and the Center for Jewish Studies works closely with the Freeman Center and the Rubenstein-Silvers Hillel, both part of Jewish Life at Duke.

Since 2001, the Center has also hosted the North Carolina Jewish Studies Seminar, bringing international scholars to campus to discuss research centered on Jewish history, culture and religion.

On top of that, the Judaica library collection and archives attract scholars from around the world with art, films, publications and archeological pieces, including one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, an impressive collection of Haggadot (prayer books used during Passover) and the papers of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. The Center even offers a fellowship for those who would benefit from access.

And the Center’s robust public programming — which shows no signs of stopping — has welcomed such notables as Elie Wiesel, Shimon Peres, Susan Silverman and Ben Ferencz, the last living Nuremburg prosecutor.

A modern take on the ancient world

Laura Lieber joined Duke in 2008 because of the reputation the university has earned in the study of Judaism and the ancient world — particularly its faculty’s awareness of the relevance of the ancient world to the modern day.

She believes that while Jewish studies holds historical significance, past events can also address the displacement and migration currently experienced in our modern world.

“When students study the Jewish diaspora, they can see historically how Jews in different parts of the world responded to different pressures,” she says. “And hopefully, they gain a deeper understanding and cultural sympathy that they take with them into the world.”

For Tyler Goldberger, a 2019 graduate of the Jewish Studies certificate program with majors in History and Spanish and now a doctoral candidate at William & Mary, the program is what allowed him to realize the vast depth, breadth and importance of Jewish studies as a field.

“Jewish studies allows us to study human interactions, behaviors and resilience over time,” he says. “Particularly in the field of genocide and Holocaust studies, Jewish studies illuminates lessons of hope and strength that can come from even some of the darkest moments in humanity.”

He hopes Duke continues to pursue an interdisciplinary approach to Jewish studies.

“The richness of the field comes when scholars and practitioners who have expertise in a number of disciplines work together to cover unchartered territory and ask new questions.”