Cemetery Citizens and the Practice of Care

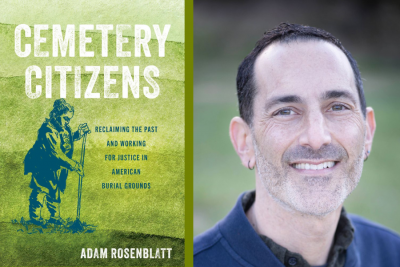

In his latest book, Cemetery Citizens: Reclaiming the Past and Working for Justice in American Burial Grounds, Adam Rosenblatt pays tribute to the volunteers restoring systemically neglected cemeteries across the country, even coining a name for them: cemetery citizens.

“I’m not a scholar who typically invents new jargon,” the International Comparative Studies professor confesses, “but I needed to explain and name a social movement that hasn’t been studied or properly acknowledged yet.”

A cemetery citizen himself, Rosenblatt documents the ongoing reclamation journeys of three burial grounds: Mount Moriah Cemetery in Philadelphia; East End Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia; and Geer Cemetery in Durham, North Carolina. Through interviews and years of fieldwork, he addresses the systemic neglect of these African American and Black Muslim cemeteries — and the work being done to restore these sacred spaces.

We sat down with Rosenblatt to learn what inspired the book, if there is a commonality among cemetery citizens and what he hopes readers take away.

Did you write this book to address a particular need in society?

I completed my first book, about the scientific investigation of mass graves after genocides and other atrocities. Soon after, the United States was living through intense upheavals with the 2016 elections and increasingly visible social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter. The protests helped shift attention to the ways Black historical narratives have been erased and distorted, and I started to think about how death and our treatment of the dead might be bound up with these issues of social justice closer to home.

One of the main points of the book is to say, as simply as possible, that the dead are still with us. People still feel the harms present when their dead are not properly buried and when their burial grounds aren’t valued and dignified. In response, though, they can claim tremendous power by caring for ancestors and their burial grounds.

It was important to bring in the voices of the people who do that physical and intellectual labor. For that reason, the book focuses on the politics of reclamation efforts, as cemetery citizens express and think about them, and less so on the history of cemeteries, burial practices or evolving preservation techniques. It’s a work of social movement scholarship and activist anthropology that highlights both the power and the challenges in the work these cemetery citizens do to honor the dead and create new kinds of community.

You acknowledge the work of diverse people who not only dig up the weeds and clean the headstones, but also dig through the archives and unearth the history of people with whom they might not share a direct bond. Is there a common thread uniting them in their altruistic work?

Cemetery workdays bring together the most intergenerational and interracial groups of people, which I really love. Our public spaces in America have been receding for a while, and the volunteers bring life, ironically, to spaces reserved for our dead. I wanted to understand why they do this work when they could be doing so many other things on a Saturday, and I’ve noticed two common threads: sharing and caring.

For example, when we’re working in Geer Cemetery, everyone brings a shared love of Durham to the tasks. And as we learn the personal stories of the people resting there, our love for the place and the work deepens.

What also binds us is the act of caring. I consider myself a scholar of care, and I’m working alongside people who are spending tremendous energy doing not only the physical jobs of clearing brush, weeding and mowing but also arts of noticing and what I call “scrappy care.” They notice where a headstone might be hidden or that a certain flower was probably planted intentionally near a grave or that a small glass bottle is not litter but rather a grave offering. They work together creatively, and sometimes with no right answer or manual to guide them, to find the best possible way to care for and dignify the spaces where they work.

I also think there are people who feel a connection to the dead. Many of the folks I interviewed didn’t have an ancestor buried in these cemeteries but did have someone, perhaps buried elsewhere, whom they were grieving. Cemetery citizens represent all walks of life and fulfill many roles when reclaiming a burial ground. The physical work often comes to mind, but the genealogical research provided by these volunteers can reunite the deceased with lost families and a broader community. Then there are the volunteers who care for the people who are caring for the cemetery by bringing McDonalds breakfast sandwiches or keeping us supplied with drinking water — so a whole series of concentric circles of care starts to build up around the cemetery.

And cemetery citizens don’t have to be human. I write about my friends’ dog Teacake, who plays an important role during workdays. Volunteers might be uncomfortable in these spaces of death, having to confront racial injustices in such stark, material ways. It can be hard to process and talk about, but then comes Teacake who just wants someone to throw her the ball. She breaks the ice and brings people together.

Is there a particular message or experience you want readers to take from this book?

I find cemeteries to be like fields of stories. When I travel, I seek them out to poke around a bit and learn the history and the structures that have, or have not, enabled care of the space. I hope readers, especially if they’ve been raised with the mainstream American attitude that cemeteries are grim and depressing places, might start to see them as beautiful green spaces full of art and history. They’re also places to grapple with the harder parts of our history and archives that speak to the strength and mutual care present in marginalized communities that had to figure out, in the face of public indifference, how to offer dignity to their dead.

And I wanted to pay tribute to the volunteers who do this dogged work, day in and day out, often with little recognition. I don’t expect everyone who reads the book to immediately join their local cemetery association; but if the book inspires readers to deepen their own practices of civic engagement, that would be great. For me, the work I do as a cemetery citizen gives me my most important communities.

Author Talk & Book Signing

Join Preservation Durham and the Museum of Durham History for a conversation between Adam Rosenblatt and Debra Taylor Gonzalez-Garcia, president of Friends of Geer Cemetery and vice president of Preservation Durham: December 11 from 6:00-7:00pm at the Chesterfield Building. Seating capacity is 50; RSVP here.