Duke-Developed Statistical Method Helps Physicians Weigh COVID-19 Treatments

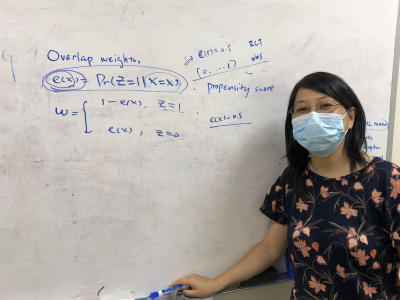

Only one line of code separates a method created by Duke Statistical Science Professor Fan Li from another methodology commonly used in assessing the relative effectiveness of medical treatments. But her approach has proved to be a powerful new tool for doctors trying to navigate complex treatment challenges for patients with COVID-19.

Li began her work with overlap weights – the name of her methodology – years before the pandemic struck. Her initial paper on the topic was published in the Journal of the American Statistical Association (JASA) in 2018. But it has gained hundreds of citations in the last two years, achieving a level of resonance that is unusual for statistical science research, Li said. Many of those citations are related to papers involving COVID-19, drawing on the methodology’s particular ability to mimic the benefits of clinical trials in determining the effectiveness of various treatments.

Li works in a field of statistics known as causal inference, also called comparative effectiveness in the medical research community. An example of research from that field would be comparing two vaccines to determine how effective they are, relative to one another, in preventing hospitalization or fatality.

Randomized clinical trials are “the gold standard” used by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory agencies in considering a new drug or medical device, randomly assigning research participants to a treatment group or a control group – those who do not receive treatment – to assess safety and efficacy. But recruitment into clinical trials can be difficult, may sometimes present ethical challenges when deciding who gets the treatment and who does not, and they can take a lot of time to execute under any circumstances – most certainly during a global pandemic. So the FDA and researchers are increasingly seeking to leverage real-world evidence in evaluating treatments.

Doctors need to know how best to treat patients who have COVID and also cardiovascular issues, or liver issues, Li explained. The health of all our human organ systems can change treatment outcomes and it would be impossible to move quickly in standing up clinical trials to address all those contingencies.

Fortunately, what physician researchers do have is a wealth of observational data. Applying statistical methods to those observations produces a representative sample and provides the insights doctors need to determine treatment – particularly when the patient’s situation is ambiguous. And Li’s overlap weights method provides that information through a simple, theoretically justified and easily-applied set of code.

The interdisciplinarity of Duke – and her connection to biostatisticians at the School of Medicine, in particular – was key to Li’s paper getting traction with the health care professionals who could most benefit from her research.

“In a situation like COVID, we cannot always conduct a randomized clinical trial but we have a lot of data that needs to be randomized,” said Michael Pencina, vice dean for data science and technology in the Duke School of Medicine. “We need methods like Fan’s that enable us to get information faster, cheaper and easier than running a clinical trial.”

Li also cited Duke biostatistician Laine Thomas as a key partner in advocating for her work and ensuring it was translatable to those engaged in clinical research.

A two-page methods brief in the widely-read and influential Journal of the American Medical Association led readers to dig deeper into her science, exploring that original JASA paper as well as one published in the American Journal of Epidemiology. Since then, Li has also created an R software package to help with running the analysis, producing graphics and generating the diagnostic data required to put her methodology into practice.

“Every method has a particular problem it’s trying to solve,” Li said. “It’s not easy to come up with something simple and generally applicable. And even if you have a good method, the gap between theory and practice is huge. People like to cling to their old methods.

“But I’m pretty pleased to be making some contribution,” she continued. “I stepped out of my comfort zone of just being a statistician (and into translational work) because I found a good method and I believe in it. I believe it will change clinical research.”

Li added that once the pandemic is behind us, she hopes the adoption of overlap weights in medical research will continue to prove helpful in treatment considerations for other illnesses.

“It has become a go-to method for comparative effectiveness studies on COVID…of course, my own goal is for everyone to realize this isn’t just for COVID – that just happened to be a timely example.”