Fighting Malaria in the Classroom and the Lab

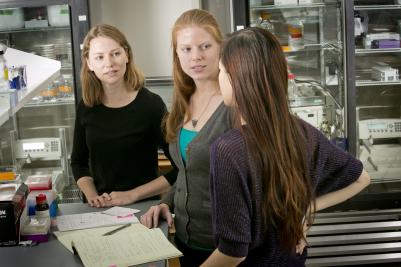

Emily Derbyshire wants to help people—and she wants to do it at scale.

Derbyshire became a professor because she felt the university setting offered opportunities she wouldn’t get elsewhere: pursuing research on diseases that drug companies wouldn’t fund and mentoring a diverse group of future chemists to expand access to the field.

In April, the assistant professor of Chemistry was named a 2020 Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar in recognition for her work on both fronts.

“I definitely felt honored and humbled,” Derbyshire said of the honor, which includes a $100,000 unrestricted research grant. “It’s distinct from some of the other recognitions, because we put a lot of time into teaching and we care a lot about our students, and there aren’t a lot of recognitions for the teaching side. That made it especially dear to me.”

Derbyshire’s focus in the classroom is overcoming the fear chemistry inspires in many students. “I try to remove any intimidation or preconceived notions about how hard it is. I think sometimes people just never had the opportunity to be taught in a way that was accessible.”

Because students enter class with a wide array of backgrounds and experiences, Derbyshire tries to make clear how much there is that she doesn’t know. “In this big world, I want to make sure they know they all have expertise that I don’t,” she said. “We’re here to share with and teach each other.”

Having taught courses that appeal to a broad audience, Derbyshire knows many of her students won’t go on to become chemists. But that’s a benefit, she said, not a drawback. “There are many other facets, beside training the scientists who will be making drugs and building new materials and optimizing more efficient energy. It’s policy. Or students talking to someone else who doesn’t know about chemistry and letting them know how important it is to all of these things in their daily lives.”

It was a related insight about what industry chemists weren’t doing that inspired Derbyshire’s current research. While she was a postdoc at the Harvard Medical School, an alarming number of people were dying from malaria across the globe. Yet profit-driven drug companies weren’t investing in malaria research—or related parasites like toxoplasma—so Derbyshire decided to utilize the resources an academic institution offered to study the disease, searching for new druggable targets that can prevent infection.

“We’re interested in understanding the path through which the parasite goes into our cells and starts restructuring the entire environment,” Derbyshire said. “What does the parasite do to the host? What does it need from us?”

To answer that question—and eventually find a way to prevent it from happening—Derbyshire focuses on what she called an “under-theorized” step in the infection process. Most research examines the way the malaria parasite infects blood cells, which is when disease symptoms begin and treatment occurs. But prior to entering blood cells, the parasite first enters the human liver. “If you can inhibit it at that stage, it’s prophylactic,” she said.

In particular, Derbyshire has found that malaria is seeking a specific protein within its human host. “There’s a human protein that the parasite turns on, transcriptionally, and then steals. If we inhibit that protein, the parasite dies,” Derbyshire said.

With the support of her Teacher-Scholar Award and other funding, Derbyshire will deepen her research into malaria in order to better understand the mechanism it uses to manipulate those proteins. But she will also explore other parasites in the same family to determine whether they all function in a related way.

“We would have an opportunity to develop a drug that will help with many parasitic diseases,” she said.