How Trinity Faculty and Students Are Sharing Resources in Support of Durham Public Schools

“Middle school girls are a lot smarter than we give them credit for,” said Mathematics major Clara Henne. “We really shouldn’t underestimate them.”

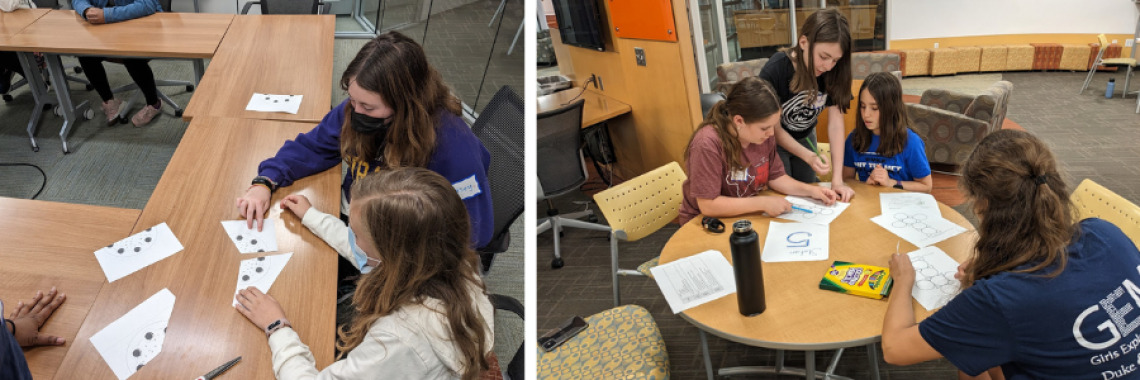

Henne learned that lesson by volunteering as a mentor with Girls Exploring Math (GEM), a Bass Connections project that offers free math enrichment workshops each Saturday at Gross Hall to girls who attend Durham Public Schools (DPS).

In addition to math problems, the workshops include interactive discussions about why women occupy a disproportionately low percentage in STEM fields, both in the workforce and across college majors — a fact that perpetuates social and economic inequity given the growing global importance, prestige and pay of many STEM jobs.

The GEM program wants to change that.

It’s also only one of many Trinity College of Arts & Sciences programs working with DPS to support student learning and expand access to educational resources.

Closing the gender gap

Now in its fifth year of operation, GEM’s leaders believe that helping DPS middle school girls feel more confident about math can narrow the gender gap in STEM. But the first step is preparing Duke students.

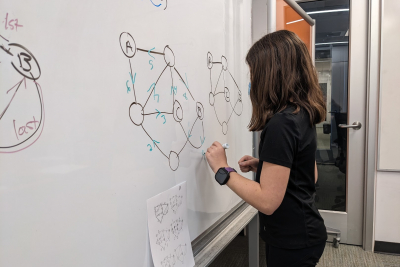

Co-directors Victoria Akin of Mathematics and Sophia Santillan from the Pratt School of Engineering teach a class called Assessing and Improving Girls' and Women's Math Identity to mentors-in-training. Building on past efforts like “Why So Few?,” a seminal report from the American Association of University Women that offers practical ways to disrupt negative stereotypes about women and girls’ STEM capacity, the course provides pedagogical skills and increased math knowledge, along with deep explorations of relevant social issues.

“Sometimes the problems we give our undergrads are just below research level,” Akin explained. “These are very challenging math problems — open questions that no one has solved yet.”

The undergraduates are required to reflect on the experience of solving each math set, identifying where they struggled or where they felt most excited. Though the math problems mount in difficulty over the term, so does student resiliency.

“Watching the evolution of our undergrads’ reflections throughout the semester is very rewarding,” Akin said.

When spring term arrives, the Duke mentees become the Duke mentors, modeling growth mindset behaviors and serving as STEM role models for their middle school students. They even adapt the problems they’ve worked on into problems for the middle schoolers. “Our math homework becomes their math homework, which is pretty cool,” Henne said.

Having female mentors at the front of the STEM classroom is intentional, because a study by Duke Ph.D. alumna and former GEM team lead Lauren Valentino shows that it has a powerful effect on female students’ likelihood to pursue STEM fields.

This was the case with Henne, who as an elementary and middle school student dreaded math. “I wasn't necessarily bad at it,” she said. “I just hated it so much. I always thought, ‘No, I'm not a math person.’”

But in high school, that changed.

“I was fortunate to have all these great female math teachers who completely changed my view on the entire subject, to the point where now it’s my major,” Henne said. “It really inspired me and got me thinking about how teachers play such an important role, especially with math, and that maybe this is something I want to pursue.”

To date, the GEM program has been able to accept every DPS middle school applicant — 60 per year — all with varying levels of math interest.

“In workshops, we don't always solve the problems, and that’s fine,” Akin said. “We're just going to explore and see how far we get.”

Most importantly, they do it in an environment — a classroom, an entire campus — of women in STEM.

Under the lights

In her first year at Duke, Theater Studies faculty member Chauntee’ Schuler Irving has hit the stage running.

With a bevy of professional acting credits, including starring roles on Broadway as Nala in the “The Lion King” and Deena Jones in “Dreamgirls,” Schuler Irving is now taking center stage in a budding relationship between the Durham Performing Arts Center (DPAC) and Durham Public Schools.

“If we aren't connecting to the local community, what are we really doing?” the associate professor of the practice asked. “Community collaboration is core to my creative process — it’s a major value for me as an artist.”

Arriving in Durham, Schuler Irving’s goal was clear: Learn where there are needs and figure out how Duke can help.

After discussions with DPAC’s office of community engagement — and with support from Theater Studies’ leadership — Schuler Irving developed a pilot program to create opportunities for DPS students to interact with professional performance artists.

“These opportunities are important because art enriches us, and I think we need to value that,” she said. “Art is not only entertainment, it’s education.”

This spring, over 200 DPS high school students attended a Q&A at Brody Theater with the cast and crew of the Broadway musical “Frozen.”

“It was a huge success,” Schuler Irving said.

The panel of theater professionals answered students’ questions about Broadway production work, different types of backstage careers and what is it like to be a person of color in “Frozen” — a question of particular relevance for many students in DPS, a district comprised of 39% African-American students and 34% Hispanic/Latino students.

Allowing space for students to discuss representation, diversity and inclusion themes with industry professionals was a key objective for Schuler Irving. “It was very honest and open, and you could feel the room kind of breathe and relax because the students really wanted to know.”

Schuler Irving also invited theater students from the Southern School of Energy and Sustainability to attend a specialty workshop at Duke with visiting artist Sheri Saunders, a musical theater coach and the creator of the masterclass Rock the Audition.

The workshop was offered to the Southern high schoolers alongside Duke students performing in Schuler Irving’s campus directorial debut.

“Bringing our students to Duke and giving them this exposure and experience was really powerful for them,” said Jesse Kirkfarmer, the theater program director at Southern. “Duke is such a huge part of Durham, and for our students to have access to some of those resources, it makes them feel confident. Even though they already have all this talent, it makes them feel like they can do this because they see other people investing in them.”

After attending the workshop, two of Kirkfarmer’s students went on to qualify as finalists at the Triangle Rising Stars Awards (TRS), an annual musical theater competition for North Carolina students where the winners advance to the Jimmy Awards in New York City — the equivalent of the Tony Awards for national high schools.

This year, Schuler Irving accepted a role as a TRS panel judge — reestablishing a pre-pandemic relationship with the program. “I used to do performance competitions when I was young, and it can be a life changing moment,” she said.

After an impactful pilot year, Schuler Irving looks forward to improving and expanding collaborations and programming. “I'm really excited,” she said. “This is the beginning of what I see as an incredible partnership with DPAC and DPS.”

Investing in the community

Former DPS high school teacher and local teachers’ union organizer Alec Greenwald helped establish community schools in Durham. As a member of the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences Academic Affairs team, Greenwald connects the community school movement to Duke, pairing higher education with local elementary schools to address barriers in equitable school experiences.

“As an institution of higher education, I think it would be criminal if we weren't trying to figure out how to leverage Duke resources to bolster and sustain public education,” he said.

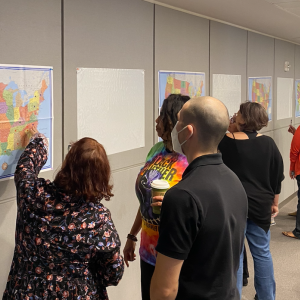

Greenwald serves as team lead of the Durham University-Assisted Community Schools Research Collective, a Bass Connections project that brings together a collective of students, faculty and staff from Duke and North Carolina Central University into a partnership with the DPS Foundation.

It’s a model that prioritizes the voices of the people that live, work and learn in that community. Families, students and teachers determine the community’s needs, which are not limited to what might be considered traditional academics. Instead, they expand to embrace whole-child education.

Together, they ask questions like: Is there a need for access to broader translation services? How do we establish an on-site vaccine clinic or family resource center? Are there childcare options? Can we invest in building greater parent leadership among families of color? What are solutions to gaining more literacy support staff?

After taking Education 101 with Amy Anderson, another of the project’s team leads and an assistant professor of the practice of Education, rising junior Emily McReynolds became a community schools believer.

The class introduced her to the political, social and economic implications that shape today’s public-school systems — and the urgent challenges they face.

“Before taking Education 101, I had no idea that property taxes funded public schools,” said McReynolds, who is majoring in Public Policy with a certificate in Markets & Management Studies. She recalls class discussions about local schools and how income levels affect poorer neighborhoods’ access to public education resources.

Of DPS’s 31 elementary schools, three have been designated as community schools: Club Boulevard, Lakewood and Fayetteville Street. Duke students working on the project serve on research subteams in support of each one. The efforts include year-long listening projects to identify the needs and hopes of the school community, developing antiracist curriculum material and creating a data dashboard specific to each school.

“The data dashboard provides a sense of the school community and its resources,” explained Xavier Cason, another team lead on the project and the director of community schools and school partnerships at the DPS Foundation. “Student volunteers can use its information to ask themselves: Do I have the right mindset walking into this community from a cultural relevance standpoint? From being antiracist?”

A former DPS music teacher and school board member, Cason describes his role on the project as a bridge builder. “I’m right there in the middle, in between the researchers and the community. My role is to make connections and help guide the implementation process.”

That process includes collecting input data from a minimum of 75% of all stakeholders in each community school, including students, staff and families. Online surveys, in-person interviews, town halls and focus groups form the baseline of the research, which all relates to local contexts.

The team is now analyzing the large collection of data it has amassed. They plan to use it to map teaching and Service-Learning resources at Duke and NCCU to the articulated needs of the DPS communities.

Recently awarded a grant from the Office of Faculty Advancement, the team continues to apply for funding in the hopes of establishing Duke and NCCU as homes in the region for university-assisted community schools. “There’s a body of colleges and universities across the state and the South that are thinking about this work,” Greenwald said.

“We’re all Durham residents,” McReynolds pointed out, “working together and collaborating on something we care about — and that's really meaningful.”