Innovative, Interdisciplinary Labs Reshape Humanities Research and Teaching

If you don’t think a laboratory is the ideal place to explore complex themes and methodologies like valuing care, ethnography, urbanism or games and culture, you may need to expand your definition beyond beakers and microscopes.

Labs are hives of communication, cooperation and active collaboration. They are driven by a commitment to curiosity and exploration that often produces unanticipated paths and solutions. And utilizing those features for research in the humanities – a scholarly area that has traditionally focused on more solitary efforts – is what Art, Art History and Visual Studies Professor Gennifer Weisenfeld hopes will be a lasting impact of Humanities Unbounded, a five-year initiative funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation that launched a series of innovative humanities labs at Duke.

The labs are one of three pillars tied to the grant. Duke is also hosting a handful of visiting fellows every year from liberal-arts colleges and historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The most recent cohort arrived in August. Additionally, the program connects Duke graduate students with Durham Technical Community College humanities faculty to offer valuable teaching experience and encourage pedagogical innovation, respectively.

As the last cycle of grant-funded labs starts up this fall, their impact can be seen in the curriculum of Trinity College of Arts & Sciences humanities and social science departments, in the experiences of Duke undergraduate and graduate students and in the attitudes of the faculty involved.

“The analogy between the scientific lab and the humanities lab isn’t perfect,” said Professor of English Charlotte Sussman, a member of the Representing Migration Humanities Lab. “But in our experience, accident and serendipity play a role in both. In each case, scholars and resources are mustered and directed towards specific goals. While those goals are often accomplished, bringing new groups of people together in the energized space of the lab can also yield unexpected results.”

Rethinking ‘productivity’ in research

The aims and activities of those involved in Humanities Unbounded labs are ambitious. Interactions spawn affiliated courses and encourage archival exploration by undergraduates. Graduate students working in the labs hone leadership and project management skills while pursuing their own research. Participants adopt new technologies and host events aimed at creating community. And it all happens in the course of a two-year cycle.

What the labs don’t emphasize is the closure or a finish line normally associated with a faculty member’s research. It’s about the process, not just a product – a journal article or book, for instance. And that has required an adjustment in approach and practice.

“It’s messy and you don’t always come out with a clear answer,” Weisenfeld said. “But the messiness is really exciting.”

Weisenfeld is one of three co-PIs on the grant, along with Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies Edward Balleisen, who is also a faculty member in History, and John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute Director Ranjana Khanna of English and Literature.

“We’re demonstrating how you go about tackling a problem,” Weisenfeld continued. “Research in action. And I think students really value that. They don’t usually see how the sausage gets made. Like with a published book, you build to that final polished product over years. But how do you get there? What’s revealed to students is how to construct a project, to build a team and establish clearly defined research goals. We even show the process of creating a class.”

“Knowledge doesn’t simply exist to be found,” Weisenfeld concluded. “It is actively produced.”

Something no one has discovered before

In the case of the MicroWorlds Lab, the knowledge the research team sought to produce sits at the intersection of history and storytelling.

Many of the exercises this lab created – which often became embedded in History Department courses – were designed to help an undergraduate design a mode of research called microhistory. Developed in the 1970s by Italian historians, it helps “get around grand narratives that lose individuals and particular circumstances to large impersonal forces,” explained MicroWorlds lab member and Professor of History Thomas Robisheaux. He was joined by fellow historians Katharine Brophy Dubois and Nicole Barnes in leading the lab, supported by other departmental faculty and a group of talented and motivated graduate student fellows.

Robisheaux said their primary goal was getting graduate students and undergraduates “really excited about research…on a scale that is manageable and where they can discover something that no one has ever discovered before.”

“And you can do that with microhistory,” he explained.

Students might be given a document from the classical period of China, for instance, or a travel narrative written by a British woman visiting Cairo. Through that source material, they would learn about and apply research methods key to working with historical documents, asking questions so they could begin to understand a story embedded in the record – the beginnings of a microhistory.

“I think the faculty, especially in the humanities, still isn’t fully aware of how eager students are for research opportunities and learning to do research,” Robisheaux added.

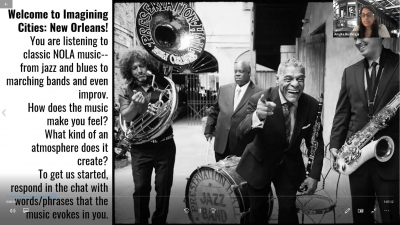

Rising Duke senior Elena Rivera exemplifies that hunger. She learned about the Visualizing Cities Lab through her major in Visual and Media Studies. Led by Weisenfeld and fellow Art, Art History & Visual Studies Professor Sheila Dillon, their lab sought to develop a dynamic approach to studying the history and culture of cities around the world, from Tokyo to Turin. Rivera joined a lab team focused on New Orleans, Louisiana.

“NOLA was known to all of us as city of food, magic and mystery,” Rivera noted. “Yet none us were clear as to why all of us – originating from different parts of the country and world – carried this imagination of the city.”

Rivera chose to specifically research the city's tie to voodoo and death, investigating cinematic perpetuation of a narrative that originated among local folklore. She said the experience also served as excellent preparation for an honors thesis.

“Each of the (lab) members had a different background and expertise, allowing for us to all learn from each other and elevate the project,” she noted. “Being an undergraduate, I am still learning about what piques my interests within my major and all the different ways in which I can apply my diverse liberal-arts education to manifest multidimensional projects.

“(Visualizing Cities Lab) was the first place in which I could experiment with all the skills and interests I have accumulated the past three years,” Rivera said.

An energetic finish

The final cycle of three new labs – an expansion from the two new labs funded in each of the previous years – will get underway on campus this fall. They are:

- “Asia” and the Making of American Religiosity: Perspectives from North Carolina – Led by Richard Jaffe, Anna Sun and Leela Prasad of Religious Studies

- Black Music and the Soul of America – Led by Thomas Brothers and Anthony Kelley of Music

- Global Jewish Modernism – Led by Kata Gellen of German Studies and Saskia Ziolkowski of Romance Studies

“We’re just ending with this fluorescence of energy that we hope will take us beyond the grant,” Weisenfeld said. “They are all really great, timely projects that will resonate with our students.”

And the students they are aiming to engage in these experiences are all Duke students – not only those already interested in the fields that have hosted Humanities Unbounded labs. Everyone is welcome.

“You don’t have to be a major to benefit from any exposure to the humanities,” Weisenfeld noted. “Just opening yourself up to this intellectual world is worthwhile.”