Duke Today

Richard J. Powell knows every artist, critic and art world star featured in the new HBO documentary “Black Art: In the Absence of Light.” He was a friend of the late art historian, curator and artist David Driskell, whose 1976 exhibition, Two Centuries of Black American Art, inspired the 90-minute special.

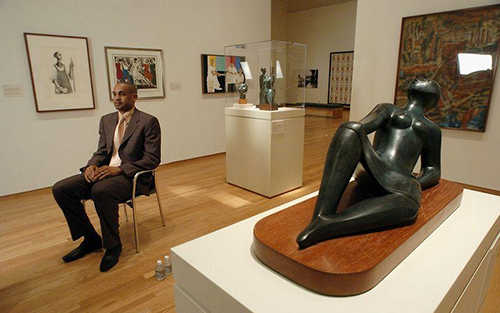

Powell also knows a thing or two about correcting outdated narratives of art history. As author, curator, art historian and professor, Powell has dedicated his career to rewriting the cannon to include Black artists who have long been excluded and overlooked by the mainstream art world.

Recently, Nasher Museum Director Trevor Schoonmaker met with Powell to talk about how “In the Absence of Light” could be a jumping-off point for more amazing stories about Black art.

Trevor Schoonmaker: Let's start with the quote from the trailer, when Maurice Berger says, “In a survey of major American museums, it was determined that 85 percent of artists in major American art museum collections are white. If you break down the number of artists of color in those collections, it's 1.2 percent Black.”

The big question is, why is this documentary needed in this moment?

Richard J. Powell: The fact that Sam Pollard got the green light from HBO to do this documentary is both a blessing and a long needed correction. I’ve often wondered why there’s never been anything that looked closely and critically at African American artists or visual artists of the African diaspora. I realized it wasn’t just the issue of a paucity of works by Black artists in museums, it was the dearth of knowledge of Black artists, their careers, their works, their struggles, their stories that meant that filmmakers hadn’t thought enough to explore those areas. With “Black Art” we had an hour and 25 minutes. I was delighted to be a part of it. There’s so much more that should be done and needs to be done and, I hope, will be done.

TS: HBO attempted to cover a lot of ground. If it were only the first in a larger series, what would you like to see as the subject of a second film?

RP: To be honest, Trevor, I don’t think I’m interested in seeing a documentary on African American art. I'm interested in seeing the stories of African-American artists, their careers, their struggles, their lives, brought to the screen. Maybe it would be more of a feature-length, fictional film. For example, Elizabeth Catlett. Why hasn't anybody looked at this extraordinary Black woman's life? Born in Washington, D.C., studied at Howard, ended up in Iowa hanging out with Grant Wood, getting involved with the Communist Party in Chicago, marrying Charles White, moving to New York, leaving him, going to Mexico, being involved with the Black Arts movement, living an incredible, long, powerful, productive life. There are African American artists throughout history who deserve a deep and complex look at what it means to be a visual maker. What does it mean to be creating at a moment when nobody really gives a hoot about who you are and what you do—and yet, you do it anyway. You persevere.

T.S.: Having the storyline of David Driskell was quite helpful to give it more depth. How can you best summarize the historic contributions of Dr. Driskell? Who was this scholar and artist?

R.P.: Let me say at the outset that Sam Pollard was absolutely right to focus on [Driskell’s exhibition] Two Centuries of Black American Art because he could take that as a launching pad and move us forward to Black Male, to the early 21st Century with Kara Walker's installation at the Domino Sugar refining plant.

But when you ask who is David Driskell, that's a much bigger story. He kind of makes his name in 1976 with Two Centuries of Black American Art but prior to that he was truly an incredible witness to how African American art might come to fruition and be better appreciated as we move from the mid-20th century onward. He was born in Georgia, studied at Howard under the aegis of James A. Porter and Alain LeRoy Locke and James V. Herring and was a student intern at the Barnett Aden Gallery [in Washington, D.C.] in the 1940s and ’50s, where he is a young man encountering the likes of Jacob Lawrence and Alma Thomas and a literal Who's Who of African-American artists. He came along at a point when the wider art world just really didn't give a hoot about what we were doing, who we were writing about, what we were interested in. He really served as a kind of a bulwark at a moment when artists needed support and encouragement.

TS: Who are just a couple of other foundational art historians and curators in the Black art world who have helped pave the way for some of today's generation?

RP: When the HBO documentary looked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Harlem on my Mind show, and they interviewed [Met curator and director] Thomas Hoving, there was a part of me that said okay now we're going to cut over to Lowery Stokes Sims, who was not there at that exact moment. But she pops up shortly thereafter and is this formidable key curator and thinker in New York City during this time period. One would have hoped that the filmmakers would have found a way to have Lowery’s insight around what it means to be a curator at an institution that, at least in the ’70s and ’80s, really didn't have any kind of deep investment in African-American art. Yet she pushed and prodded the various directors and others to acquire work in a yeoman-like way.

T.S.: Can you name one other exhibition that's been pivotal, influential and sort of changing the game in the last 30 years?

R.P.: Kongo: Power and Majesty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2015. When they did that Kongo show they really did their homework. They told a story of a Black diasporic moment that spanned centuries of interaction between Europe and Central Africa, the fusion of Christianity and traditional African beliefs. They were able to borrow all of those fantastic Nikisi Nkondis. The Kongo show was a fresh, brilliant and delightful immersion for me into an aspect of the African diasporic visual experience, a very narrow one, looking at Congo.

T.S.: What do you see as the primary opportunities and challenges for young scholars, curators and practitioners going forward, in this moment?

R.P.: I would say that what faces the young scholar is the charge to really make an impact. I would argue that to make an impact one should go for the tough road, as opposed to the easy road. The easy road is to kind of put your ear to, not the ground, but to your computer, and to see all the faddish and hip stuff that's happening, and you do your version of that. I remember Kerry James Marshall saying this in the auditorium at the Nasher: Do something that nobody else is doing. Do something that's really going to stand apart and set you apart in terms of your contribution to the field, to the discipline, to the culture.

I’m going back to David Driskell. He plugged ahead for years and years when he taught at Fisk doing important shows, writing about people, interviewing people. Nobody gave him the time of day, you know, at The New York Times or at HBO. But he knew it was important. He knew that he had to make his contribution, and we are all the better for him forging in that direction.

T.S. This is a perfect place to stop. There's a beautiful closing statement!

R.P.: Thank you for the invitation to chat. Thank you for making Duke a place where those of us who are interested in the arts of the African diaspora can thrive and imagine. Thank you!

Watch the trailer of “Black Art: In the Absence of Light,” directed by Sam Pollard