‘Truth is a Linguistic Question’ Talks by Five Trinity Scholars Relaunch Series on Language Discrimination

More than 50 people gathered in a Duke classroom both in-person and remotely this September to consider whether “Truth is a Linguistic Question” – a prompt provided by faculty leading the ongoing Sawyer Seminar Series on language discrimination in fragile and precarious communities.

Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the series launched in spring 2020 and continued throughout the pandemic thanks to a combination of perseverance and the power of Zoom. This latest seminar kicked off a slate of events for this fall. And the next is scheduled for October 14 at 5:30 p.m. in Social Sciences 139 and via Zoom.

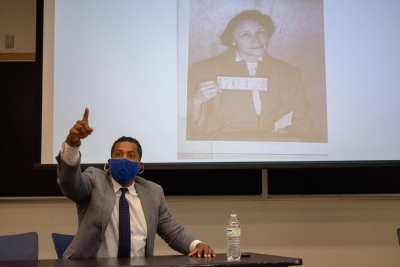

The talks featured at the September panel were limited in length but the discourse was powerful, with speakers considering topics of race, history and linguistic diversity. Leading off was Martin Smith, dean of academic affairs for Trinity College of Arts & Sciences and an assistant professor of the practice in the Program in Education.

How we teach Black history

After sharing a bit about his own relationship to the U.S. South and aspects of American schooling that have been historically contested, Smith displayed two historical photos. One depicted the ruins of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, bombed by Klu Klux Klan members in 1963. The other showed police with dogs confronting a man at the Children’s Crusade – also known as the Children’s March – that same year.

“This broke the back of segregation,” Smith said of the latter event. “If they didn’t march, I’m not here. So why don’t people know about this? Or often, people know about the bombing, but they don’t know about the march. In what ways is Black history framed as suffering and not agency?”

He made a similar comparison between photos of Rosa Parks – whom members of the audience immediately recognized – and Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, who started planning bus boycotts in Alabama six years before Parks’ arrest.

“Was your education true if you learned about Rosa Parks but not about Jo Ann Gibson Robinson?” Smith asked. “If we don’t know these stories, was your schooling experience truth?”

Varying views of bilingualism

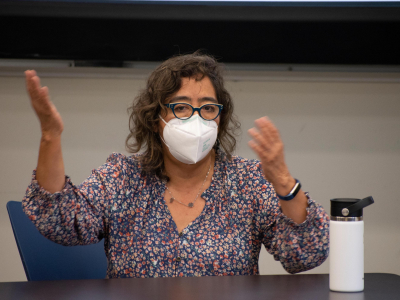

The research that has shaped the career of Liliana Paredes, professor of the practice of Romance Studies, emerged from observations about her native Peru.

People who immigrated to the capital city of Lima from more rural areas were identified as indigenous and marginalized based on their use of language. She seeks to understand the effects of that discrimination had on those speakers in schools and other social systems.

By contrast, she is struck today by how bilingualism is held up as an asset – but only in certain contexts.

“Why does the Spanish I learn at Duke have extra value for my career?” Paredes asked attendees. “It’s framed as a skill…but when we hear people speaking Spanish or any other language outside our doors, then we think ‘why are they not speaking English?’ Why is that bilingualism negative in our minds?”

“It happens often in the U.S. with Spanish…Spanglish – is it positive or negative? The question is, who decides? But at the same time, people are marginalized for using that version of Spanish or that version of English. When we marginalize because of language, we are not inclusive.”

National languages and perceived threats

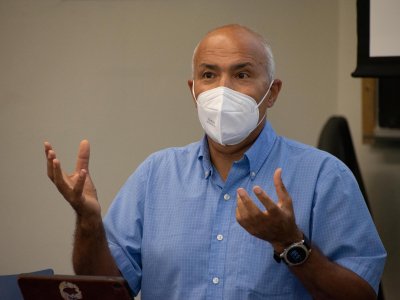

Although Abbas Benmamoun may be best known at Duke as Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement, his scholarly expertise lies in language as a professor in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies. His talk focused on the perception and reality of declaring a language “endangered” – particularly in the Arab world.

“When there is a linguistic anxiety, that may be real,” he said. “The loss of linguistic diversity is an issue. It is a real issue. This country used to have hundreds and hundreds of languages spoken and passed down through generations. But in other places, there is nuance. There is history and there is perception.”

Benmamoun shared a few graphics featuring emotional appeals about the Arabic language being under threat, though research shows it is still incredibly strong – particularly when compared to other languages spoken in North Africa, such as Berber or Aramaic. He noted that an increase in English in schools and universities is one factor adding to that myth, as well as growing support for preserving regional dialects.

“Multilingualism was the way of the world for many, many years. And we can deal with it. Multilingualism is the reality. When you open space for another language you feel like your language is being threatened – that there is only space for one.”

“We tell our students to seek truth,” he added. “But you have to have an open mind, to embrace complexity and be able to tolerate nuance in what we look at.”

Confronting linguistic myths

The presentation by Edna Andrews, professor and chair of the Program in Linguistics, started with a primer on myths that have been debunked in her field dating back to 1926 and continuing up to 2015. They include the presumed inferiority of immigrant groups, a proliferation of racist, sexist and agist theories and more.

“This is part of the migration and immigration story of the United States,” said Andrews, who comes from a family of Greek immigrants. “The myth of monolingualism has never been true. But in that frame, all of us who come from families who did not originate in the United States have gone through difficult moments when you are shamed because you speak another language. And when you are told by your parents, ‘Speak English!’”

She went on to further address persistent myths about the monolingual brain and bilingualism in children. Now, Andrews said, we know about cognitive flexibility, and that children who speak more than one language actually benefit – even if they are participating in two different speech communities within the same language.

“We need to return people of color and different genders back to the story,” she said. “This is an ongoing battle. We still live with these lies. Code-switching is normal, code-switching is healthy. There’s nothing wrong with it.”

Race and racism in the U.S.

Lee D. Baker, professor of Cultural Anthropology and African & African American Studies, closed the series of talks by digging into specific historical moments that exemplify race and racism in America.

“Something that makes people crazy is when people say that America was built on a lie.” Baker began. “Maybe it wasn’t a lie, but it was a fabricated truth.”

He displayed a slide featuring a set of postage stamps emblazoned with the U.S. flag and the words freedom, liberty, equality and justice. Slavery and the Indian Removal Act “really destroy those notions,” Baker noted. “There were certain people who were created equal. And others? We can explain that away.”

He walked the audience through a brief history of race and rule in early America – from the colonization of the Americas and false notions of racial hierarchy up through the Declaration of Independence and the Louisiana Purchase.

“It was a simple thing…we were going to take Native Americans’ land and African Americans’ labor,” he said during a Q&A period following the talks. “We needed both.”

“You’re taking them away not just from their land, but from their livelihood – their life, really. It’s just an example of how ravenous racism can be to maintain white supremacy.”

View previous talks from this Sawyer Seminar Series on the Focus Program website: https://focus.duke.edu/talks-and-lectures-mellon-sawyer-seminar-series