What Decolonization Means

When Michaeline Crichlow moved from her native St. Lucia to upstate New York, she had a lot to learn — and not just in the graduate program she attended at Binghamton University.

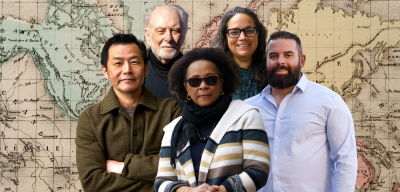

“I became a Black person not in the Caribbean, but in the United States,” said the professor and interim chair of African & African American Studies.

Race wasn’t often discussed in St. Lucia, where the vast majority of the population is Black. The rare times it was, the conversation wasn’t about Black and white, but the Indo-Caribbean peoples descended from the small number of Indian indentured servants brought to the island in the 1800s.

Crichlow didn’t begin thinking seriously about race until she read about South African apartheid and the Sharpeville massacre while in detention in the school library. Blackness, for her, was a consciousness that came through those horrific developments in South Africa.

Yet, other Caribbean nations generated very different experiences. Crichlow’s Jamaican partner, who she joined in Binghamton, was the first to tell her “you better start thinking and learning about how race is lived in this country,” she said. With a notable white and mixed-race elite, Jamaica offered him “a greater sensibility of racialization.”

Other islands were different still. “St. Lucia is not like Trinidad or Suriname or Guyana, which had a whole lot more indentured people — Indians, Chinese, Indonesians and all these people the British or Dutch thought would resuscitate plantation production in the wake of the abolition of slavery,” Crichlow said.

Walter Mignolo experienced similar differences himself — twice.

Born and raised in a small town in Argentina to an Italian immigrant family, he was assigned a new identity when he crossed the Atlantic to pursue a doctorate at the École des Hautes Études in Paris.

“In France, I was a sudaca,” he said. “That is the name given to people coming from Latin America, from the south (sud).”

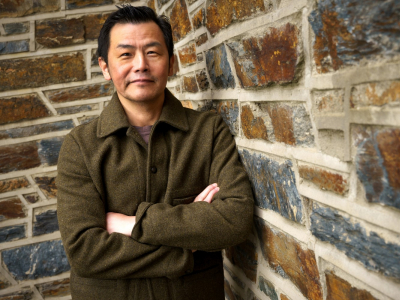

When Mignolo moved to the United States, eventually joining the Duke faculty as the William Hane Wannamaker Distinguished Professor of Romance Studies and professor of Literature and Cultural Anthropology, he gained other descriptors.

“Here, I was a Hispanic,” he said. And it’s shifted some since, as American understanding of Central and South America has evolved. “Latinx, Latino: it didn’t exist at that time,” Mignolo noted.

What governs the ever-fluctuating identities assigned to Mignolo and Crichlow are the colonial lines drawn across the world map over the past centuries. Today’s world was shaped by the colonialism, from its political borders and cultural transmission to its migration patterns, economic organization and lines of credit.

“Even when people aren’t invoking colonialism, they are pointing to the outcomes,” Crichlow said.

A growing movement seeks to “decolonize” contemporary institutions in order to reckon with those histories, and a number of Duke scholars are untangling what that requires. Taking different, sometimes contradictory approaches, they are connected by the belief that colonization and its end aren’t a matter of the past, but an ongoing project for the future.

The many meanings of decolonization

Understanding decolonization begins with understanding the term, which isn’t as simple as it first appears.

Usage of the word has risen precipitously in recent years, but there are also related terms and movements, like postcolonialism and decoloniality, which have distinct meanings. Often, those terms have arisen in different places and times in response to perceived failures of previous movements.

Originally, though, “decolonization” referred specifically to the historical period in which colonial governments were deposed.

“It is a historical period that really happened, that really existed, and a series of events that profoundly shaped the world we live in today,” said Samuel Fury Childs Daly, an assistant professor of African & African American Studies, History and International Comparative Studies. “But it wasn’t just one thing.”

A historian of postcolonial Africa, Daly emphasizes that “there were many different forms of decolonization,” including “decolonizations of the left and the right.”

As an example, Daly points to the military men he’s writing about in an ongoing book project, provisionally titled Soldier’s Paradise: Africa Since 1966, which investigates the regimes that ruled Nigeria and other former British colonies in the late twentieth century.

“In these soldiers, you can find a lot of the tensions and antimonies in decolonization,” he said.

Trained in British military academies, they revered the tradition inherited from their former colonizers at the same time that they spoke the language of radical anticolonialism, more often connected with left-wing figures like the philosopher and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon.

Fusing the two elements together, Nigeria’s “decolonizers” in uniform inaugurated a complex movement that Daly believes cannot be reduced to simple binaries.

For instance, after taking power as a dictator in the 1980s, Muhammadu Buhari launched the “War on Indiscipline,” encouraging citizens to form orderly lines at bus stops and show up to work on time, among other things. Buhari’s government — filled with rank-and-file soldiers disappointed with the white-collar bureaucrats who originally took power after independence — believed it was a necessary step toward freedom.

“Buhari talked about it as a kind of radical, revolutionary transformation of society from the ground up,” Daly said.

But Buhari also enforced the campaign with harsh disciplinary measures. Soldiers literally policed street corners with whips.

“So what was militarism’s true nature?” Daly asked. “Was it a conservative, discipline-and-punish strategy or something more radical? In order to understand it fully, we have to see that it was both.”

The question has a particular resonance today: after being overthrown in 1985, Buhari re-entered politics in 2003 and has served as the president of Nigeria since 2015.

The space of the hyphen

Responding to those complicated, state-led movements, a new generation of postcolonial activists and academics demanded more fundamental changes. The goal was not to resist Western governments, but to build new models of governing altogether. And that meant rejecting the nation states that defined the 20th century.

One particularly influential school, called subaltern studies, coalesced around South Asian thinkers like Dipesh Chakrabarty and Gayatri Spivak. Focused on everyday people rather than the halls of power, the project aimed to show how populations who were oppressed and minoritized were the agents of their own history, not just pawns of the elites — whether European or domestic.

Originally inspired by studying “history from below,” Jessica Namakkal demonstrates the value of such an approach in her recent book Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India.

By focusing on the former French colony of Pondicherry, not only does the associate professor of the practice of International Comparative Studies, History and Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies revise the timeline of decolonization — “I suggest we should see it as a movement, not a moment,” she said — but she also complicates the usual story of Indian nationalism in the anti-colonial movement.

Pondicherry, home to a majority Tamil population, remained in French control for 15 years after Indian independence. The French had also offered citizenship to its colonial subjects in an effort to prove they were better colonizers than their British competitors, so by the time of independence, some Pondicherry residents had been French citizens for generations. (Notably, residents of other French colonies like Algeria were not given the same rights.)

But it was mostly the low- and under-caste people who exercised the option. “People that were upper-caste Hindus did not want to convert,” Namakkal said. “They thought that would sully their caste status.”

As a result, the story of decolonization in Pondicherry is a story of people with complicated loyalties. Namakkal writes about Raphael Ramanyya Dadala, a Dalit — a term used by people who live under caste oppression — who was taken in by a French priest before working as a police officer. Yet, he fought against France during the independence movement, citing Joan of Arc as his justification.

“He takes inspiration from all this French history he’s learned to fight for his own country, which is India,” Namakkal says.

But after independence, his Dalit identity came to the fore and he was treated terribly. So he turned his attention to fighting caste oppression within his newly claimed country.

“There are all these different identities people inhabit, often in the same person,” Namakkal said. “A lot of people switch their allegiances a lot, because there’s no firm idea of the national subject.” That indeterminacy is especially true for the population of Tamil French Indians, who occupy what Namakkal calls “the space of the hyphen.”

Decolonizing decolonization

One irony about postcolonialism is that, even as it offered a strong critique of Western imperialism, it remained tied to the Western world.

In part because of the history of the academic fields that nurtured it — the interdisciplinary area and cultural studies departments created in the midst of the Cold War — areas outside of Western concerns remained obscure. That included the Japanese Empire.

For Leo Ching, who was beginning his academic career in the 1990s, when postcolonialism was the school of thought du jour, that realization was the entry point into decolonization.

“The focus was almost exclusively on British, French, Dutch, Spanish colonization,” said the professor of Asian & Middle Eastern Studies, who also serves as the director of International Comparatives Studies. “Even [famed postcolonial scholar] Edward Saïd’s important Culture and Imperialism has maybe two sentences on Japan as a global empire.”

Including Japan in a discussion of colonialism deepens our understanding, Ching argues. Because Japan barely escaped colonization itself before launching a massive colonial project in its own non-Western image — while explicitly drawing from American and British advisers — it offers a novel view.

“It’s not simply that Western colonialism excluded Japanese Empire,” Ching said, “but rather that when we bring it into the fold, what will colonialism look like? Even within the critique of the West, there’s this lurking Eurocentrism that cannot imagine that you can have a non-white colonial power.”

Drawing on popular culture, Ching investigates the emotional valences of the Japanese imperial project across East Asia, beginning with his native Taiwan in Becoming Japanese: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation and more recently in 2019’s Anti-Japan: The Politics of Sentiment in Postcolonial East Asia.

His finds that the relationship to Japanese empire varies across countries, and even within families.

On the one hand, Japan’s brutal subjugation of China — marked by bloody massacres like the Rape of Nanjing — created a strong anti-Japanese sentiment. Beginning with Mao’s regime, the Chinese Communist Party’s success in fighting Japan became a hallmark of Chinese nationalism.

When some of those Chinese nationalists established a regime on Taiwan, they brought their anti-Japanese beliefs with them, forming an official discourse that painted Japan as obvious villains.

Yet Japan ruled Taiwan as a colony of its own for nearly 50 years, emphasizing infrastructure building as a way of proving that its colonial efforts benefited the native population, and thereby proving Japan’s prowess on the geopolitical stage. As a result, many Taiwanese look back fondly on the Japanese regime as a more humane era, in distinction to the ongoing Chinese rule.

“Growing up in Taiwan, a lot of my own relatives had this tremendous respect and intimate relationship with Japan that was completely erased from the official discourse,” Ching said.

The world within the Caribbean

In all of these cases, the question of colonization and decolonization tends in two directions: toward the most personal relationships and experiences on one hand, and toward sweeping, global trends on the other.

The two are inseparable, as Crichlow’s life and research have made clear.

“I’m looking at the world from the Caribbean, because the world’s in the Caribbean and the Caribbean’s in the world,” she said. “I never ever forget the fact that my unit of analysis is the world.”

The statement bears the marks of Crichlow’s education with historical sociologists Terence Hopkins, Immanuel Wallerstein and Dale Tomich. The three scholars are prominent advocates of world-systems theory, which analyzes world history not primarily through the lens of nation states, but through the international division of labor and the world capitalist economy more generally.

“I’m interested in projects of development as having the capacity to let a minority of people escape poverty, a minority of people get rich, a minority get state largesse, while the vast majority have a foot on their necks and are vulnerabilized,” Crichlow said.

Currently, Crichlow is researching the experience of Haitian migrants working in slave-like conditions on contemporary plantations in the Dominican Republic. To understand how they ended up in that position, she says, you must understand a centuries long narrative.

It begins with the slaves who formed the Caribbean’s first modern labor force and the sugar market driving the plantation economy that lasted from the 17th through the 19th centuries in the Anglophone region. But the Dominican Republic’s history is different. There, plantations started earlier — in the 16th century — but didn’t really take off until the late 19th and early 20th century, when they used wage labor.

That global — and still ongoing — history set the stage for the extractivist policies of 20th century dictators like Haiti’s Papa Doc Duvalier, the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo and the long cast of leaders who followed in their footsteps violently exacerbating Caribbean socioeconomic inequality.

Those conditions, in turn, have been used to justify the US and World Trade Organization trade policies that, combined with stringent conditions on International Monetary Fund loans, have indebted Caribbean economies today — all of which has been made worse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It has exposed the deep and structural faultiness of the high-growth developmental model,” Crichlow said. “Postcolonial countries still find themselves locked into relationships that reproduce development models that promise a lot, but have delivered very little.”

As articulated in books like 2009’s Globalization and the Post-Creole Imagination: Notes on Fleeing the Plantation, Crichlow instead tries to find a path toward a better future by asking, “What are the central pivots through which subjectivity, agency and power are being worked out, creatively reproduced, morphed or transformed” by those most impacted by global inequality and enduring colonial relationships.

“My point has been and still is to stress the contradictory and open ended-ways that people work out those strategies of getting beyond,” Crichlow said. “And that has to do with whatever action is undertaken to unsettle and rupture colonial forms of thinking and existence, that fix hierarchies which rationalize and justify uncaring approaches to people, species and the more than human world.”

Ways of knowing and being

For Mignolo, the important realization in those narratives was not merely about the world, but about the way the world is understood in the most basic sense “in the hegemonic structure of knowledge.”

“I began to realize that something was not as I thought,” he said of his time in France completing a Ph.D. “I was a foreigner, not just in legal issues, but in feeling. This is not my language. This is not my history.”

The problem didn’t begin in France, though. Mignolo grew up reading the leading lights of U.S. and European letters — Camus, Kafka, Steinbeck, Faulkner — thinking they were the height of culture. He went to France because that’s where he thought learning took place, not in South America.

“Many years later, I began to understand how self-colonized I was, how coloniality worked in me,” he said.

It began in 1995 when he encountered the ideas of Peruvian thinker Aníbal Quijano, whose work on the “coloniality of power” inspired a new avenue that Mignolo has been following ever since, leading to a slew of acclaimed books like The Darker Side of Modernity, Local Histories/Global Designs and last year’s Politics of Decolonial Investigations.

Mignolo argues for “decoloniality,” which he says is a way of meeting head-on “the underlying logic of all Atlantic, Western colonialism since 1500.” The point is not to discover a particular history, nor to make certain political demands — something that he says sets it apart from decolonization movements and postcolonial theory. The goal is nothing short of “epistemic and ontological reconstitutions.”

“We are looking at the deepest structure of North Atlantic colonialisms,” he said.

Coloniality goes so deep, Mignolo argues, that it’s embedded in not just in every institution of the modern world, but in the very ways of thinking and being assumed to be natural since the Renaissance (in Christian theology) and the Enlightenment (in the secular sciences and philosophy). This “colonial matrix of power,” as Mignolo calls it, has made rationalistic, Western thought the standard for all people, undermining the value of non-Western beliefs, knowledge and ways of knowing and living.

As a result, Mignolo’s decolonial project requires “delinking” from the colonial matrix of power. Doing so depends not just on reasoning, but on what Mignolo calls “emotioning” to emphasize the substantial degree of transformation away from rational individualism.

“Once you get out of the binary either/or and of the primacy and privileges of the Ego, you begin to think in a different way because you begin feeling in a different way; you discover the biology of love and reject the culture of hate,” he said.

The aim is “communal conviviality among ourselves and with planetary life,” which Mignolo hopes to reconstitute by working with collaborators from across the globe, and particularly those of Indigenous and African descent who birthed decoloniality, through institutions like the Center for Global Studies & the Humanities.

“The communal is the reemergence of the organization of people in relation with Earth and the cosmos and all the living,” he said.

Toward a future that recovers the past

With their different outlooks, schools and areas of analysis, each of these scholars has different aims for their work.

On the one hand are historians like Daly, who says his hope is that he can communicate “the tensions in this story, and an appreciation of the fact that its characters can’t be neatly divvyed up into sellouts and revolutionaries.”

Rather, by examining decolonization, he hopes to make clear that “as soon as you scratch beneath the surface, you find that people are making compromises and making choices. They’re not always the choices you’d expect.”

On the other, there are theorists like Mignolo, who is focused on changing the way people relate to the world around them.

Describing the impact he hopes his research and teaching can have, Mignolo tells a story about an undergraduate in a class he taught on indigenous cosmologies who was inspired to focus on the sounds of the natural world during his walk to class rather than listen to music, as well as a Chinese student who reconnected with his language and culture’s traditional medicine.

For Mignolo, those everyday acts are the first steps toward finding the necessary communal ways and practices of living.

But despite the differences between these scholars, there is also tremendous overlap. Mignolo and Ching have co-taught often throughout their time at Duke and in Kunshan, Crichlow and Namakkal make use of decolonial concepts within their historical research and all draw from — and critique — the historians and theorists of decolonization and postcolonism who came before them.

What puts all of their work in conversation with each other is the belief that analyzing the colonial forces that shaped this world can offer new routes for a better future.

“To understand the rootedness of empire,” Namakkal said, “not just abroad but in Durham, in North Carolina, in the United States, you need to understand not just the history of colonialism, but colonialism as an ongoing project.”