When Science and Art Meet at the End of the Road

Lichens, just like Chantal Harvey, thrive in the proximity of the sea.

The Canadian artist lives in the small village of Baie-Johan-Beetz, along the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in the Côte-Nord region, far north along the Atlantic coast of Canada. Her house wouldn’t be out of place in a late-night Zillow dream. It’s a luminous red building planted firmly on the bare bedrock, mere feet away from the rolling sea and surrounded by water-carved monoliths and that hard and scrawny vegetation that seems to scream, “Life isn’t easy, but I am strong.”

Among that vegetation, lichens rein supreme. Growing almost flat against the rock, they resist the gale with ease and aren’t particularly appetizing to herbivores looking for a snack before the winter. They get the water they need from the rain and fog that rises from the cold sea.

Harvey, who spent her career seeking ways to bring the beauty of nature to those who live removed from it, saw them. She truly, really saw them.

“I can’t even step on them anymore,” she said. “I became obsessed. I would stop, look at them, just see all their colors on the ground, and then I asked myself, ‘Why am I not working on this? It’s too pretty, too extraordinary, for me to be the only one who notices it!’”

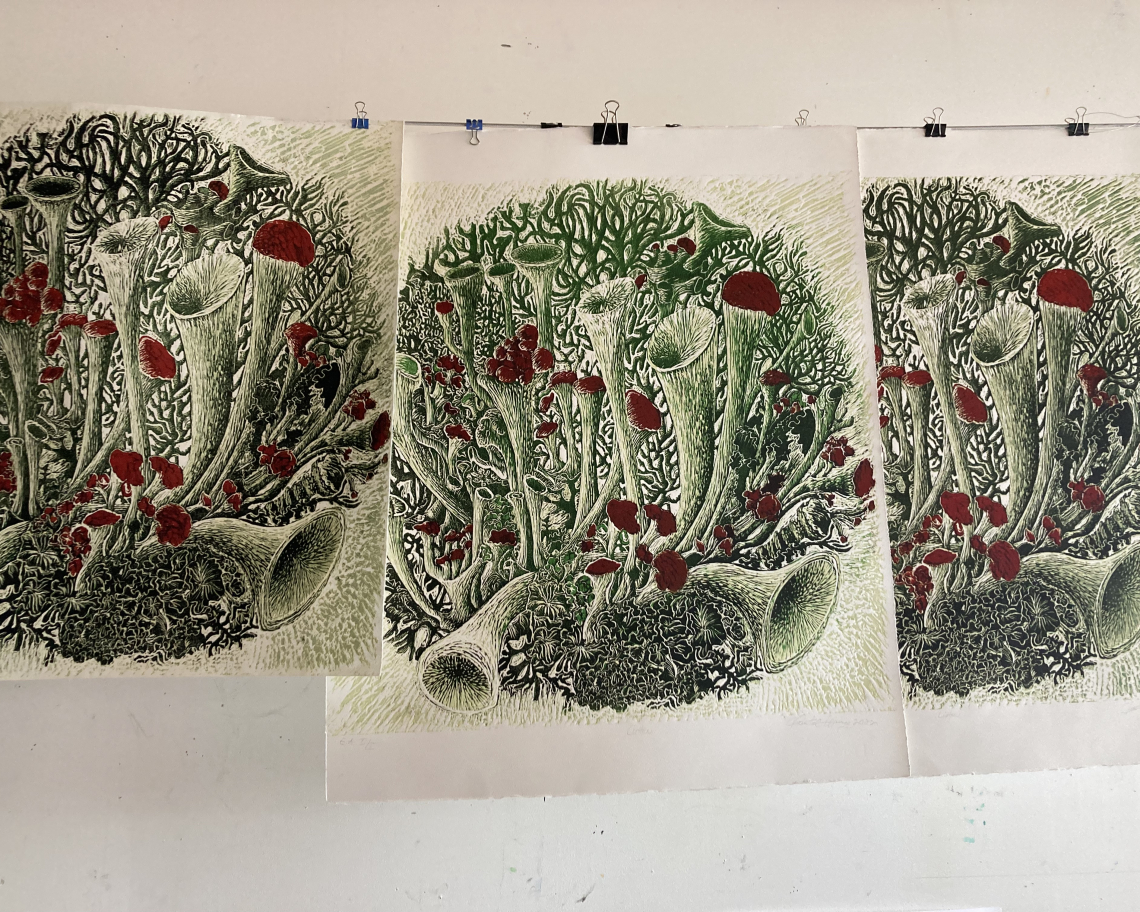

Harvey started taking pictures of the lichens she observed on her long, daily walks and had them printed in poster size. Then she turned them into art. With the help of a grant from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec (CALQ), she put together an entire multidimensional exhibit called Lichen, for which she received the CALQ’s Artist of the Year Award.

And that’s when François Lutzoni’s phone rang. The lichenologist and professor of Biology, who is from Québec, was greeted by his sister, eager to share the news she had just heard: a Québec artist had won a national award with an exhibit entirely about lichens. She sent him a video (in French) about Harvey and her exhibit, and Lutzoni was hooked.

“He came to my office and he told me, ‘You wouldn't believe it, there's this person, this artist, who is inspired by lichens!’” said Lutzoni’s wife and longtime collaborator, Jolanta Miadlikowska, a research scientist and instructor in the Biology department.

Lichens weren’t the only connection Lutzoni felt with Harvey. Nearly 40 years ago, he passed by Baie-Johan-Beetz on the boat that served villages without road access all the way up the coast of Labrador. “I felt like I had arrived home,” he said of the region.

Lutzoni returned to do field work in the area 10 years later, then again 20 years ago, with Miadlikowska.

Back then, boat, helicopter and snowmobile were the only way to access Harvey’s village.

“When we were doing field work there, we had to just stop because the road didn’t exist,” said Miadlikowska. “And so we were always thinking, ‘We should go back and continue our travel as far as we can to explore.’ And here was Chantal [Harvey] living right there.”

Lutzoni sent Harvey an email, introducing himself as a fellow lichen loving Québécois.

“I was really touched,” said Harvey, “realizing that this was someone who pretty much dedicated his life to lichens, who studied them for 40 years, and who is not only interested in my art, but wants to know how he can contribute to my own research and my own discoveries.”

They scheduled a Zoom call. She told them that she wasn’t done with lichens. She felt there was more, but didn’t have a very concrete plan yet. Maybe if they met in person, they’d give her more inspiration? She had good news too: the road now reached her village, greatly simplifying the logistics of a potential visit.

After some inevitable pandemic-related delays, this past summer Lutzoni and Miadlikowska loaded a microscope into their car and tackled the 1,600-mile drive from Durham to Baie-Johan-Beetz.

“There were lots of sentiments going back to our past field work sites, checking how much the place has changed, how much it had developed,” said Miadlikowska. “We even stopped at the same pizza place for lunch!”

Excursions into the wild are a big part of the two lichenologists’ yearly routine. Their research focuses on the evolutionary, ecological and genomic basis of lichen’s symbiotic association between algae, or cyanobacteria, and fungi.

Understanding how any given group of organisms evolved from a common ancestor to their current forms is always tricky: Imagine assembling a gigantic puzzle where more than half the pieces were lost, a quarter haven’t been found yet and the remaining ones could disappear at any moment. The fact that lichens aren’t a single organism, but a symbiotic association, greatly increases the puzzle’s complexity, so every summer, Lutzoni, Miadlikowska and their graduate students canvas the globe looking for puzzle pieces.

“Every time we are in those exotic places where we collect, everything is complex,” said Miadlikowska. “There are collaborators, the whole team, and we run from place to place, and we have a schedule and we’re rushing, and we always say, ‘Oh, we have to go back just for the beauty, just to be able to admire it,’ but there’s never time.”

Harvey, with her keen eyes and the sensibility of those who find beauty literally under their feet, is the exact opposite.

Their encounter was a revelation.

“It was a luxury to be there, to have time to walk around, to just admire, listen and just learn from the way Chantal looks at nature,” said Miadlikowska.

“Chantal’s relationship with nature is different,” said Lutzoni. “We are very much ‘denatured,’ right? We're separated from nature, but she, and people that live immersed in an environment like this all their lives, have a very different understanding of the natural world, of actually being part of it. It's not even an understanding, it's a way of living.

“When she looks at nature, it's the beauty of it that’s art itself.”

While Lutzoni and Miadlikowska learned to look at the whole, Harvey’s revelation came from zooming in.

“Looking at lichens under the microscope really, really touched me. I got a bit emotional,” said Harvey. “It was my first time seeing them so large, and at that scale they really become even more grandiose, an entire world that we never see, so tiny, but so complex, so fascinating.”

Harvey left their encounter not only with inspiration for her next exhibit, but also with lichen samples that she plans to display side-by-side with her art.

“If people see the real thing in a museum, maybe they’ll get a better understanding of how fragile they are,” said Harvey. “They’ll maybe start asking themselves questions: ‘Where will this go? With climate change, how will they respond, how will they move in space? Will they even still be here in 20 years? They are so delicate!’”

Gesturing out her window, facing the sea, she continued, “All I want in my work as an artist is to share that with people. I want the world to see it, to be sensible to nature, to protect it, because, you know… it’s fragile.”