A New Minor Prepares Students to Take on an Unequal World—in Any Field

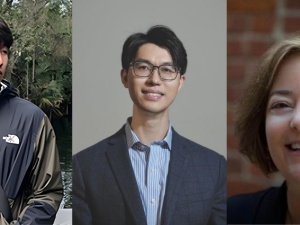

For Drew Greene, it started with the children he coached in high school.

He was part of a soccer program for youth in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. When his players told him about their siblings who had been sent to jail for simple school-yard fights, Greene was inspired to start investigating the school-to-prison pipeline. That interest led him to join the Henrico County Equity and Diversity Advisory Committee in his senior year. He hoped to help address the racial, gender and socioeconomic disparities in his school district.

“I just really loved the people,” said Greene, who is now a first-year Duke student. “I loved how everyone was so passionate about it.”

When he got to campus, Greene thought he would study finance. Then he took a class with Adam Hollowell, adjunct instructor of Public Policy and Education, and he realized how deep his passion for fighting inequality ran. “Especially now that inequality is at the forefront of people’s minds because of the Black Lives Matter protests, I want to work to find solutions for major issues,” Greene said.

In addition to planned studies in Public Policy and Education, Greene found a brand new program that would let him do just that: the Inequality Studies Minor.

Launching this semester, the new minor is a collaboration between the Department of History and the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity. Directed by Hollowell, the minor was also shaped by Malachi Hacohen, professor and director of undergraduate studies in History, and William A. Darity Jr., Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy, African & African American Studies and Economics and director of the Cook Center.

“The study of social inequality is more urgent than ever, especially if higher education is to fulfill its mission as a promoter of expanded opportunity and well-being,” the three scholars wrote in a December op-ed for Inside Higher Ed. “Students, professors and administrators need a deeper understanding of how human disparities have developed, why they persist and how they continue to evolve over time.”

To provide that knowledge, the minor requires classes on the history of inequality, methods for studying the subject and a research initiative, alongside historical electives that cover additional aspects of inequality across history.

“We want liberal-arts education to speak to the contemporary world,” Hacohen said. “The major challenge we face is to show how inequality is historically created and is not to be taken for granted.”

The program pairs that historical insight with contemporary research opportunities. “The minor is a particularly strong way to help students think about the meeting point between research they do across the university and the history of inequality in social science and humanities research as a whole,” Hollowell said.

Those two elements make the minor a particularly compelling option for students like Madi McMichael. The first-year plans to go into medicine, either as a forensic pathologist or a surgeon, so she’s particularly interested in health disparities.

“I think it’s important to understand how these inequalities can affect people’s health, how they manifest in certain diseases or predispositions to certain diseases,” she said. She’s planning to add the minor to her pre-med course load, alongside her volunteer work at the Pauli Murray Center and blogging for the Duke Medical Ethics Journal.

The diversity of Greene and McMichael’s interests is just what the faculty have in mind for the program. “I would like Duke graduates, future lawyers and bankers, to be permeated with the notion that when they make their decisions, they affect patterns of inequality,” Hacohen said.

More than anything, though, the program is a response to what Duke students are interested in.

“What I want to honor and respect is the extent to which the students are asking us to do better in teaching them,” Hollowell said. “I think this change is a part of a broader reckoning of academic study amid an unequal society.”