Haley Warren, Trinity Communications

After teaching Romantic Fairy Tales: Literary and Folk Fairy Tales from Grimms to Disney for many years, Professor Jakob Norberg became fascinated with the Brothers Grimm not only as folklorists but as members of a particular generation of German nationalist scholars and thinkers.

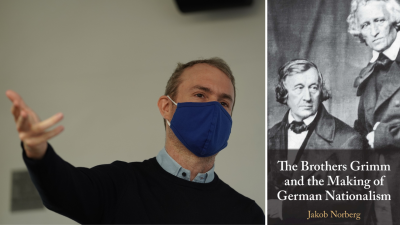

His new book, The Brothers Grimm and the Making of German Nationalism, presents his research about two of history’s most famous storytellers. Through historical analysis, Norberg reveals how the Brothers Grimm used their writing — including their folk tales, fairy tales and linguistic works — to help construct and define national identity and German nationhood, weaving a political agenda into their works even though they might not appear explicitly political.

Norberg, current chair of the Department of German Studies, spoke with Trinity Communications about the evolution of his new book and how he hopes to reframe the Brothers Grimm for an audience who might not be familiar with the political impact of their work and writing.

I think that without the Brothers Grimm and their generation of scholars, we wouldn't really have something called German studies today. Before them, people didn’t study national literatures in exactly the same way. People would learn Latin, they would learn Greek, they would study the classics and they would also learn multiple languages and read literatures. But the idea that the way to slice culture was according to nationhood, or linguistically so that you should have a German language department and maybe a Spanish and French Language Department or Russian or Slavic language department, that was a novel idea.

You could say that the discipline that I am in right now, German studies, is about 200 years old and they were pioneers of this study. So in some sense, this book about the politics of the Brothers Grimm is an exploration of the origins of the department that I'm in today.

One thing that struck me is that they had long term professional identities. If you see the images of them and if you just know this incredibly famous collection of folk tales and fairy tales, you think of them as storytellers, as people who gather the tales of the people, put together a book and then disseminate these stories among the people again.

But when you look at the professional identities, you realize just how long and how often they worked at courts for particular princes and kings in Germany. They were trying to alert the German people to their own national identity and their own stock of stories, but they were at the same time trying to bring a message across to the princes and kings and telling them about the people that they were ruling. They were saying “you need to be aware of the ethnic, cultural, linguistic character of the people that you are ruling, and you need to create policies and rules and govern in a way that is respectful and sensitive to the cultural character of that people.” And so they were trying to awaken the people, but they were also trying to subtly influence the kings.

I tried to place the Brothers Grimm in their time between the people and the ruling elites. They have these ambitions of being influencers or advisors to ruling elites. I think that's new in in the book and something I was struck by and interested in.

I'm really fascinated by the very first Walt Disney full length animation feature, the 1937 Snow White. When you realize how aware they were the cultural legacy of the Grimms, and how much they worked to capture that visually in an animation feature for the first time, and how many of the visual artists they employed were actually European exiles who were themselves steeped in this tradition, it's really a fascinating document. And you know, from the Brothers Grimm to Walt Disney might seem like a huge leap, but there aren't that many decades between Brothers Grimm and Walt Disney. And the way that Disney tried to encapsulate the spirit of the folk tales visually really fascinates me.

One thing that I noticed is that when students come in and want to take the fairy tale course, they associate fairy tales with romance – that it's somehow about love in their minds, maybe finding the right person and kind of experiencing the first love.

And if you read the fairy tales, yes, they usually do end with a marriage. But the fairy tale in its entirety is about a process of maturation. So that the fairy tale starts with a moment of exile or expulsion and then there's a series of obstacles and challenges that the heroines and heroes have to overcome usually with the help of some other figure. And then at the end there's a reincorporation – a reintegration of this person into a new familial context. And so really, the stories are about the paths of maturation. And they're really not about romance.

I think that's something that resonates with the students and that they can relate to their own lives. They can kind of see that there is an elemental pathway that we follow when we go from childhood through adolescence to adulthood and that the fairy tale is less about the moment of falling for someone or the romantic moment.

Fatherhood is such a dramatic change. It provides you with an entirely new identity and with a set of responsibilities that define your life and that completely changes your perspective on reality. It's just a defining factor in my life – that I'm a father. That's how I see it.

And I like some of the stories because often they can be told from different angles. There is the story of Sleeping Beauty. When you read it as a child or a teenager, maybe you think it's about you. But when I read it as a father, I thought, well this is about the protectiveness of a father. And maybe it's about the overprotectiveness of a father – someone who is so cautious and so focused on protecting his daughter, that he removes everything that can hurt her.

I think a lot about how these stories tell tales of childhood and parenthood and maturation, and how they also tell us to be protective, but not overly protective, to expose ourselves to dangers but not be reckless, and things like that. That's all part of these tales, because they're fundamentally about family formation.

And so I enjoy teaching these stories that are about the formation and dissolution and re-formation of families. They are about the fundamental relationships of human beings: about being a child in relationship to an adult, being a sister in relationship to a brother, being a son or daughter in relationship to a father or a mother.

And in some ways, the stories tell us that to be a human being is to be in those relationships.

Professor of German Studies Jakob Norberg is the author of The Brothers Grimm and the Making of German Nationalism, published through Cambridge University Press and available through open access. His course on Fairy Tales from the Grimms to Disney is typically offered in the spring.